All installation photos: John Brash

Gallery : Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition : Peter Kennedy Chorus: From the Breath of Wings

Curated by Juliana Engberg

above: Installation view; right: “The Presence of the Past”, 1993

A major exhibition presented at the Fifth Australian Sculpture Triennial, Melbourne, 1993; taking as its subject the end of the Cold War (when everything changes) it references totalitarianism, the past, present and future and uses loudspeaker imagery as well as Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History” as recurring motifs.

Important: A selection of works follow. Other works featured in this exhibition, but not included in the following, can be viewed in this site’s Film and Video section.

Note: Catalogue essays on Chorus: From the Breath of Wings by Anne Marsh and Bernard Smith, are in the Selected Articles section on this site.

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

1. Siren; The North (after Mayakovsky)* 2. From left: The Golden Light of the East, The South

3. From left: The South, The Golden Light of the East, Icarian Dreamer – with fallen words

4. From left: The South, Grave of the Enlighteners (middle), The Golden Light of the East, Village Voice (far right, background)

* Siren; The North (after Mayakovsky) can be viewed in the Film and Video section of this site.

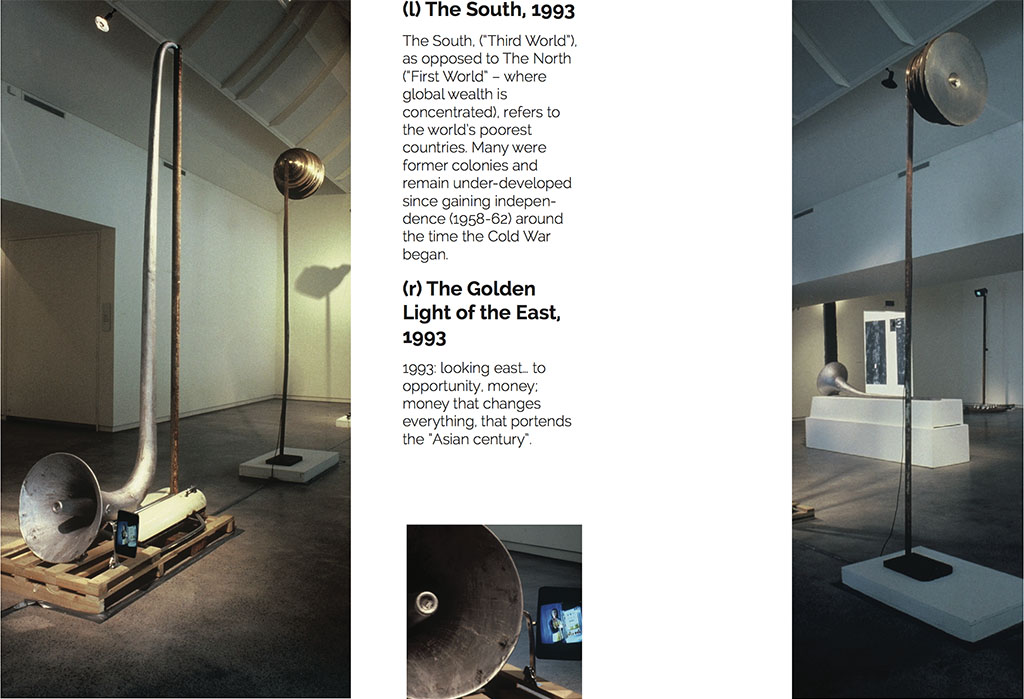

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above left: The South: painted aluminium alloy loudspeaker with matching painted Styrofoam extension, attached to steel pole and mounted on car door (with rear vision mirror, set to reflect the television screens of “The North”, placed opposite), and fixed to timber pallet.

Middle: The South (detail)

Above right: The Golden Light of the East: eighteen brass cymbals (of graduated diameter) mounted on steel pole and base with small speakers / resonators and amplified, tape recorded sounds.

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above: main picture, detail (left) Grave of the Enlighteners: painted aluminium alloy loudspeaker (silent), with matching painted Styrofoam extension, plinth.

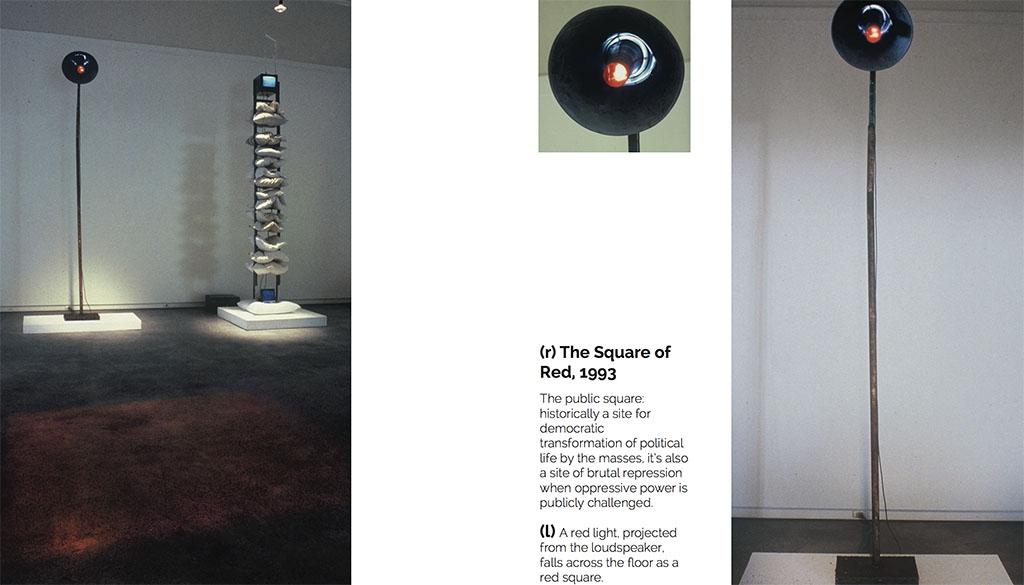

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above left: The Square of Red (at left) … and the utopias They rise into the sky and turn pale* (at right).

Middle: The Square of Red (detail)

Above right: The Square of Red: red light fitted to lens and inserted into aluminium alloy loudspeaker, mounted on steel pole and base.

* “… and the utopias…” can be viewed in the Film and Video section of this site.

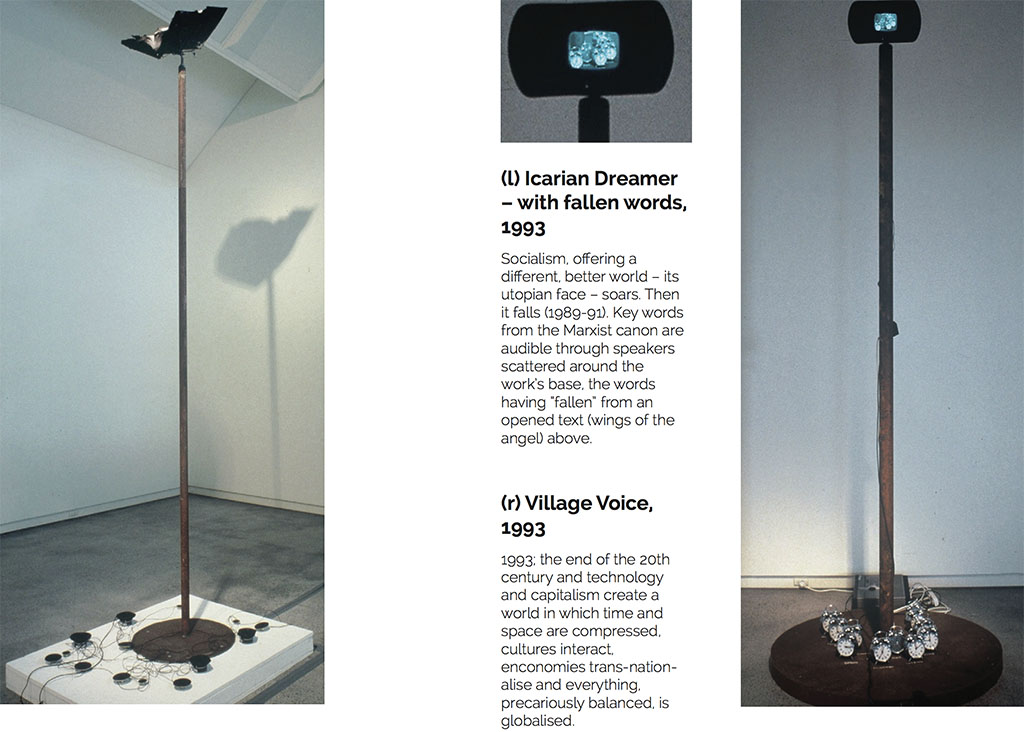

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above left: Icarian Dreamer: with fallen words; opened book (burnt front and back covers) mounted on music stand attached to top of steel pole, steel base with small speakers and tape recorded words.

Above right: Village Voice: 5” black and white television inserted in loudspeaker and mounted on steel pole and circular Masonite base with clocks and closed circuit security camera.

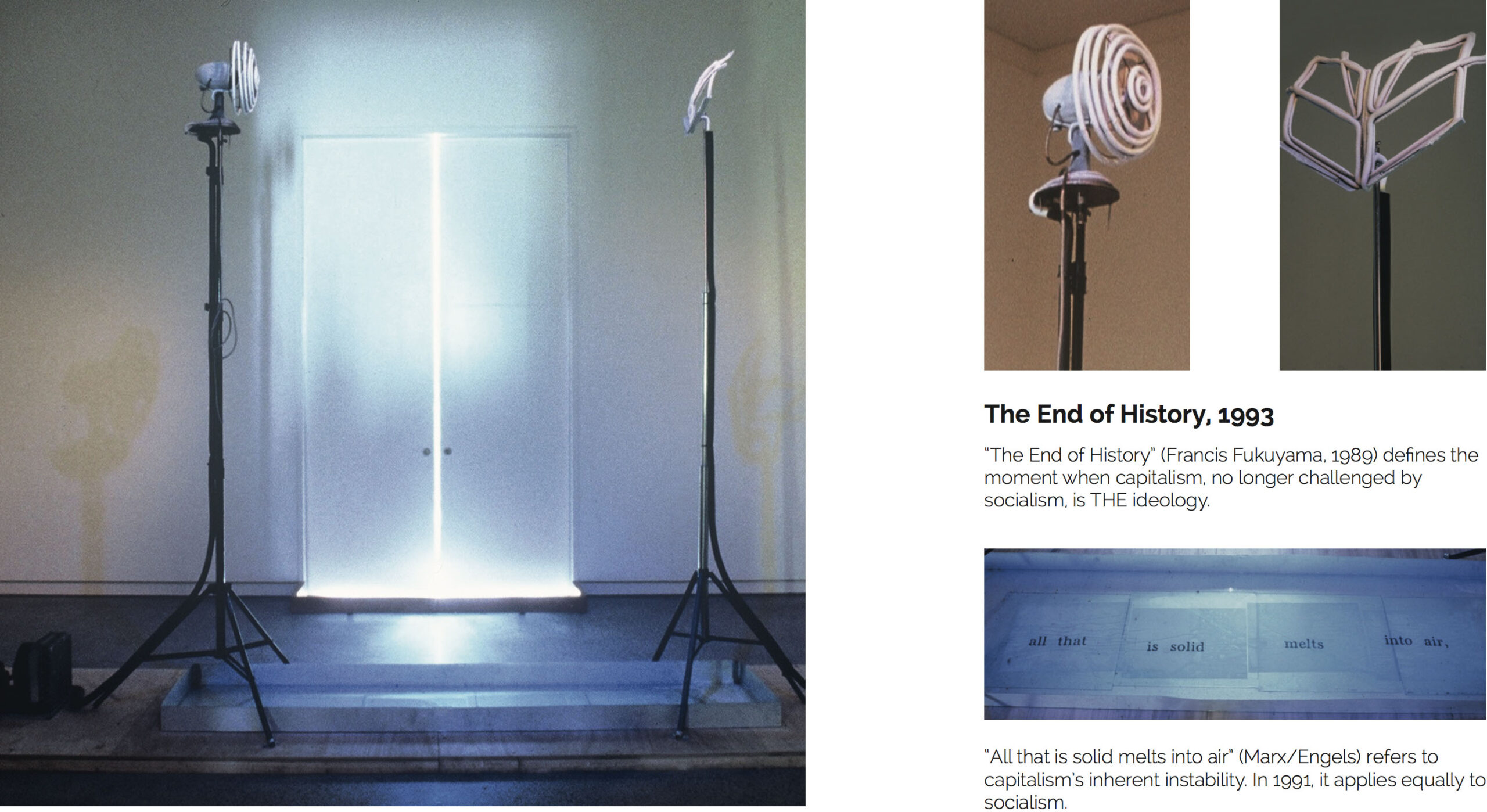

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above left: The End of History, 1993: above right (details)

The End of History, 1993: refrigerated electric fan, music stand (reconfigured as angel’s wings) mounted on tripods above a metal box gutter containing water with submerged words “all that is solid melts into air” and set on plywood platform.

Gallery: Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993

Exhibition: Peter Kennedy Chorus: From The Breath of Wings

Above left: Emissary (formerly ‘Angelic Emissary’): degraded aluminium alloy loudspeaker mounted on steel pole (method of mounting is variable, site specific) with electric fan.

Middle: Canon: books (burnt), loudspeaker mounted on wood batten (loudspeaker is silent, wiring visibly unconnected), partially blackened/burnt, wood grain laminated panel on four castors.

Above right: Canon: (detail)

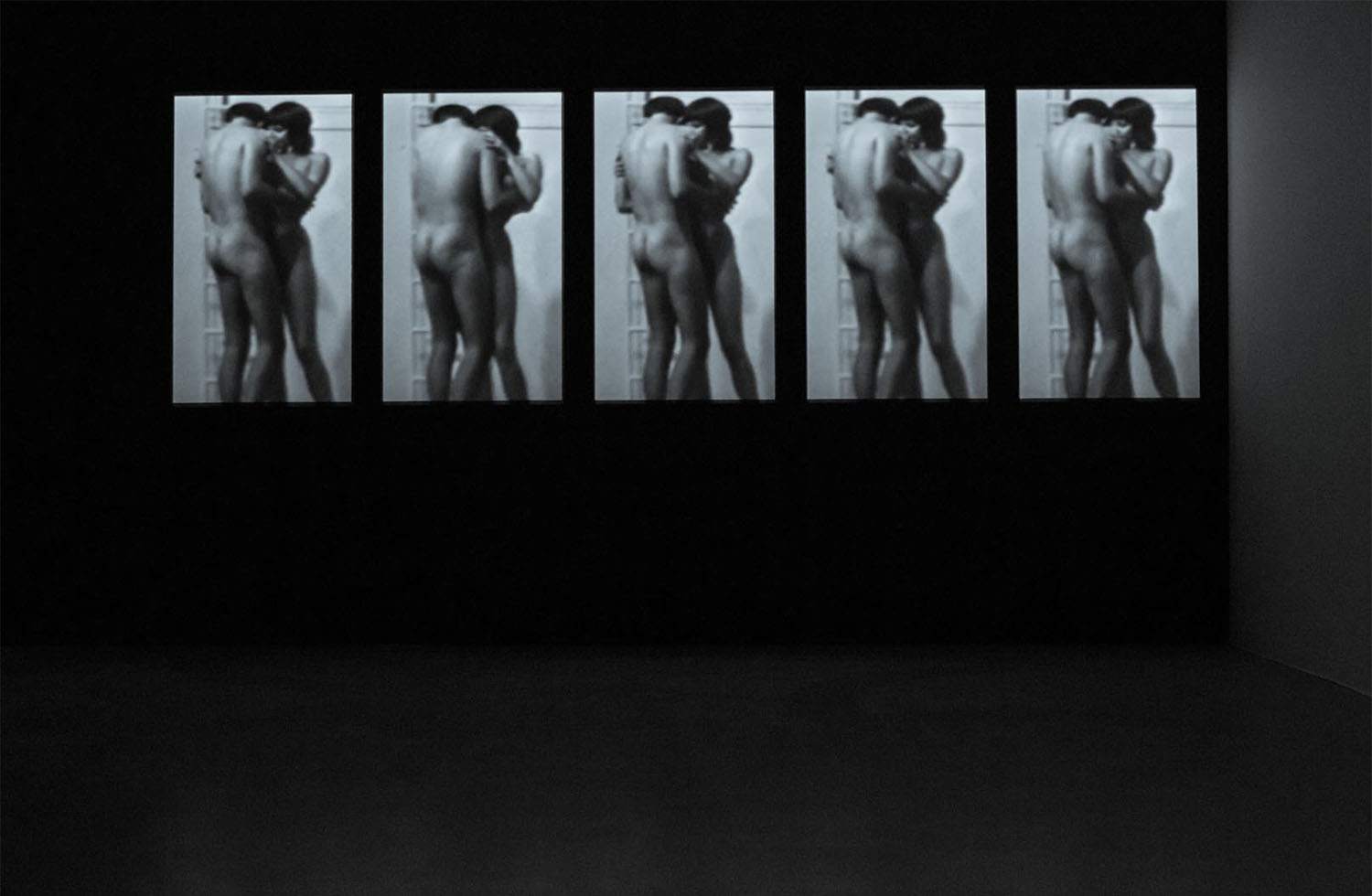

Body Concert Part 2 Extended 1971 - 2015

Single channel digital video and sound, 6:28 min, dimensions variable, edition 3

Body Concert Part 2 Extended reinterprets an original 1971 video work* where two performers manoeuvre a contact microphone between their bodies while relying on the pressure of their embrace to ensure its mobility.

The microphone in both versions (1971 and 2015) is responsive to the performers’ movements and what is heard can seem at odds with the subtlety of the action. As this later version progresses, so does the sound: the abrasive sounds at the beginning evolve into a listenable musicality at the end. Extension of the original work also includes its visual re-composition – five, discrete frames with staggered timing provides a rhythmic visual element to the performance.

* Body Concert 1971 can be referred to in the context of other 1971 video works by returning to the Film and Video section of this website.

Installation photos at Inhibodress, Sydney, 1972

Snare 1972

Snare drum, side drum, chair, amplifiers,

tape deck, speakers, drum sticks, photographs; dimensions variable

Collection: MCA, Sydney; TATE, London

A leading figure in the world of mid-twentieth century avant-garde theatre, playwright Eugene Ionescu (1909-1994) observed: “Modern art’s avant-gardists’ attack on bourgeois values and culture was always destructive in its intent. History, however, shows that this aim ends up being assimilated and absorbed” by that same dominant culture.

“Snare” plays with this tradition of artistic intention and cultural assimilation. Aggressively anti-bourgeois in its conception,

“Snare” challenges the reality of assimilation, not through any disagreeable visual presence, but rather by sonic assault – in recognition of the futility of alienating a contemporary audience by visual means alone.

Passive and benign to begin with (the trap) it then unleashes a barrage of discordant drum sounds and feedback. This, then, is “Snare’s repudiation of bourgeois culture’s propensity for assimilation.

Installation photographed at Peter Kennedy’s THERE THEN HERE NOW exhibition, Milani Gallery, Brisbane, 2019

Snare 1972

Snare drum, side drum, chair, amplifiers,

tape deck, speakers, drum sticks, photographs; dimensions variable

Collection: MCA, Sydney; TATE, London

‘Snare’ takes its name from the snare drum at its centre. This drum has a microphone placed underneath it and a speaker inverted on two drumsticks that rest on top. Another speaker is magnetically attached to a steel-framed chair, facing the snare drum. Both speakers are attached to an amplifier which is connected to a two-track tape deck.

Track 1 plays an original drum solo which is heard through the speaker on the chair. The second track is a decayed version of the original solo and its recorded performance – the method used to achieve the decayed effect – is shown in the photographs displayed on the adjacent side drum.

The decayed track is played through the inverted speaker, the sound being projected into the drum itself. The resonance this creates vibrates the snare attached to the drum’s underside and adds to the ‘noise’ that the microphone, through an additional amplifier, feeds to a third speaker. This speaker is housed in a conventional speaker box of the period and its positioning – the same applies to the other equipment – plays a role in the installation’s spatial design where feedback (sound) is a contingent element.

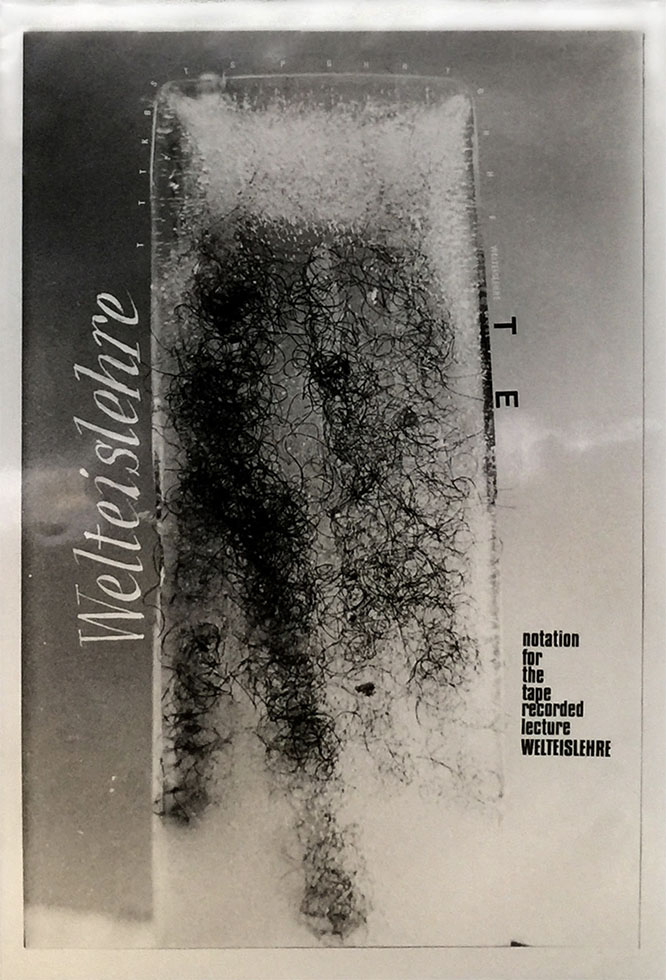

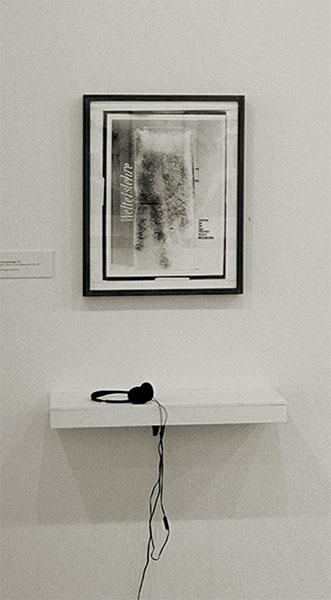

Welteislehre 1972

World ice learning: world ice theory

Black and white photograph with hand lettering,

Letraset, tape recorded voice, headphones 40.6 x 50.8 cm

Private collection

Exhibited at Inhibodress, Sydney, in 1972 in the exhibition “Idea Demonstrations Peter Kennedy Mike Parr”. Welteislehre engages with the opposite of truth at the time Germany was governed by Nazis. For the Nazis, the Theory of Relativity was a problem because its author, Einstein, was a jew.

Their answer was to come up with an alternative theory and an institution to proclaim it. The Academy for Welteislehre was to be that institution. Werner Heisenberg, a Nobel prize winning physicist, famous for the principle of uncertainty, would be the director. The Academy’s purpose was to promulgate a Nazi conviction that the stars were made of ice – a theory that had never quite gone away from the time it was first espoused in the decade prior to 1900.

Welteislehre’s sound component has a recording of a man’s voice telling the above story in German. At the end of the story he stops speaking but remains a presence behind the microphone. The listener hears street sounds, occasional voices, including a child’s, perhaps a car horn or siren and maybe there is a dog barking. The sounds outside are mundane. The owner of the voice is still present. The listener hears him swallow.

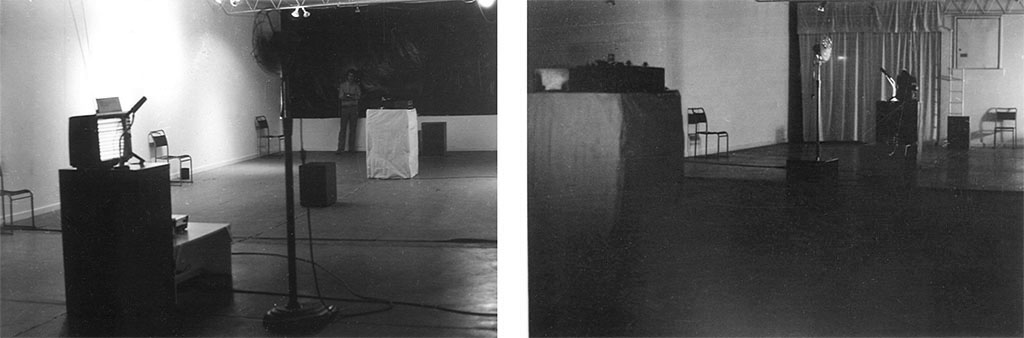

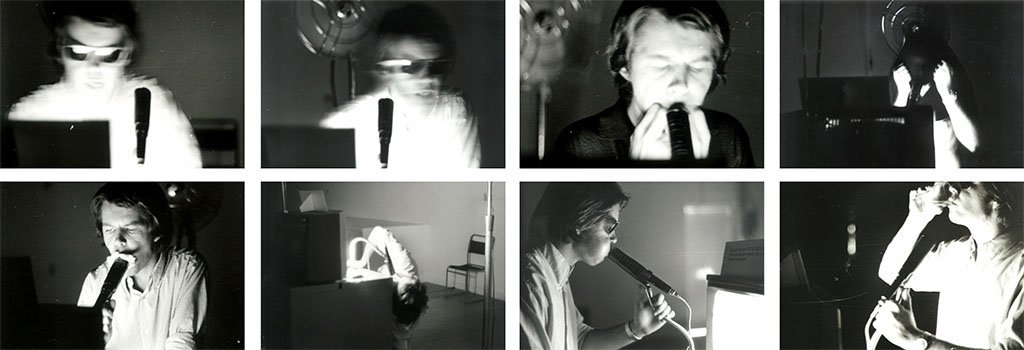

Contact sheets. Photos taken in March, 1971 at Inhibodress, Sydney.

But the Fierce Blackman 1971

Tape deck, 1⁄4” magnetic audio tape loop, microphones, amplifiers, speakers, b & w television set with rabbit ears aerial, oscillating electric fan, artist performances, audience participation.

Collection: MCA Sydney; TATE London

But the Fierce Blackman, an installation with performance, was first staged in March, 1971, at Inhibodress, an artist-run gallery, in Sydney. The work consisted of an arrangement of speakers, a portable television, a tape deck, a looped audio recording, oscillating electric fan, amplifiers, and microphones.

It is the earliest example of a sound installation by an Australian artist as was the inclusion of video. At the time, artist performance and audience participation – important components of the exhibition – were new and unfamiliar.

One wouldn’t know how well Peter Kennedy has made his thing (‘But the Fierce Blackman’) for the very good reason that it is quite unclear what sort of thing he has made. It’s very weird and powerful; and for whoever would like to know what’s really happening in art now, the answer is, in a way, simple. This is.

Donald Brook, The Sydney Morning Herald, Thurs., March 11, 1971

… More daringly than most other Australian artists, (Kennedy) grapples directly with the bare bones of sound and space. If it is true that “stripping down” is one of the major impulses in 20th century art, then Kennedy here shows a way of extending it beyond what was thought to be the terminus – minimal art.

Terry Smith, “Good exhibitions were rare in 1971”, The Review, December, 18-24, 1971.

Installation photos taken in March, 1971, at Inhibodress, Sydney

But the Fierce Blackman 1971

Collection: MCA, Sydney; TATE, London

INSTALLATION DETAILS

The television was tuned to a regional broadcast channel for the purpose of receiving a degraded reception – a strategy that produced ghosted images, static interference and raster patterns while also providing the only light in the space.

At regular, brief intervals, the fan would blow the television’s ‘rabbit-ears’ antenna against two wires fixed at the back of the television and connected to the ceiling. These wires played a role in the creation of visual noise and static sounds whenever the antenna contacted them. At the same time, taxi radio calls were picked up and heard live as they were transmitted from taxis operating in the area.

A tape deck played a loop of an amplified spoken phrase ‘but the fierce blackman’. Heard in combination, these amplified sounds filled the space. Added to this mix were two microphones and a P A system. One microphone picked up static from the television’s speaker. The other microphone was used for the artist’s performances as well as for audience participation.

Installation photos taken in March, 1971, at Inhibodress, Sydney

But the Fierce Blackman 1971

Performances involved repetition of the phrase ‘but the fierce blackman’ spoken into the microphone. Performing over three weeks allowed for various vocal experiments with a different constraint or stress – to break the natural rhythm of the voice – being applied each night. The sound of the phrase, spoken between gulps of water or muffled by a shirt pulled over the head and held against the mouth, or tissues, cardboard, fingers placed in the mouth – varied according to the method of intervention. Assuming stressful body positions or, in one instance, running up and down stairs to become breathless, were some of the other techniques used to distort vocalisation of the phrase. In addition, audience members were invited to participate by injecting their own vocal responses into the mix.

During the previous year (1970), in an experimental session with the group AZ Music, I committed myself to an act of planned randomness by drawing on one of John Cage’s (1912-1992) central ideas concerning the role of ‘chance’ in art making and read out loud the first words I saw on a scrap of newspaper picked up from the floor. Those words ‘but the fierce blackman’ were repeated, mantra like, for the duration of that experiment.

CONTEXT: THEN AND NOW

An idea about art that was in the air in the mid-1960s and still influential in the early 1970s: art could scale back on meaning, on the necessity of context, even on the necessity of content. The work itself could be enough. Susan Sontag wrote in ‘Against Interpretation’ (1964) “We must learn to see more, hear more, feel more. Our task is not to find the maximum content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing.”

In this context, “But the Fierce Blackman” is its own truth. It was what it was. But sensation was inevitably intrinsic to the experience and intimations of darkness, mystery, fear or anger, flight, or even light, for instance, could be a part of it. Or maybe not. At the time, it didn’t matter.

Now, fifty years later, that newspaper line on the scrap of paper might be construed as reflecting larger social concerns and racial attitudes. There were, at the time, doubts within society that were new and troubling. Crime, organised and otherwise, was on the rise or so the newspapers would have it – correctly, as it turned out. Talk of dystopian cities made people feel unsafe. A troubling fact too, was that Australians and Americans were still fighting an unpopular and unwinnable war in Vietnam. Social inequality was entering the minds of more people, particularly inequality as it applied to indigenous people. Here, a long shadow was cast over a deep wound and those demanding redress were increasingly numerous and active.

And now history books tell us that the ground was laid around 1971 when institutions of liberal democracy began to be reconfigured in a way that benefited the few while causing social inequality to expand and become entrenched.*

Peter Kennedy, January 2021

*Simon Reid-Henry cites 1971 as an historical marker in this context in his book Empire of Democracy – The Remaking of the West Since the Cold War 1971-2017, published 2019.

Photo taken at Peter Kennedy Selected Works 1970 – 2002, The Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne

But the Fierce Blackman 1971 - 2002

Documentation of installation and performances:

photographs, headphones, CD players and sound recordings made at Inhibodress, Sydney, in March 1971

Collection: UQ Art Museum, Brisbane

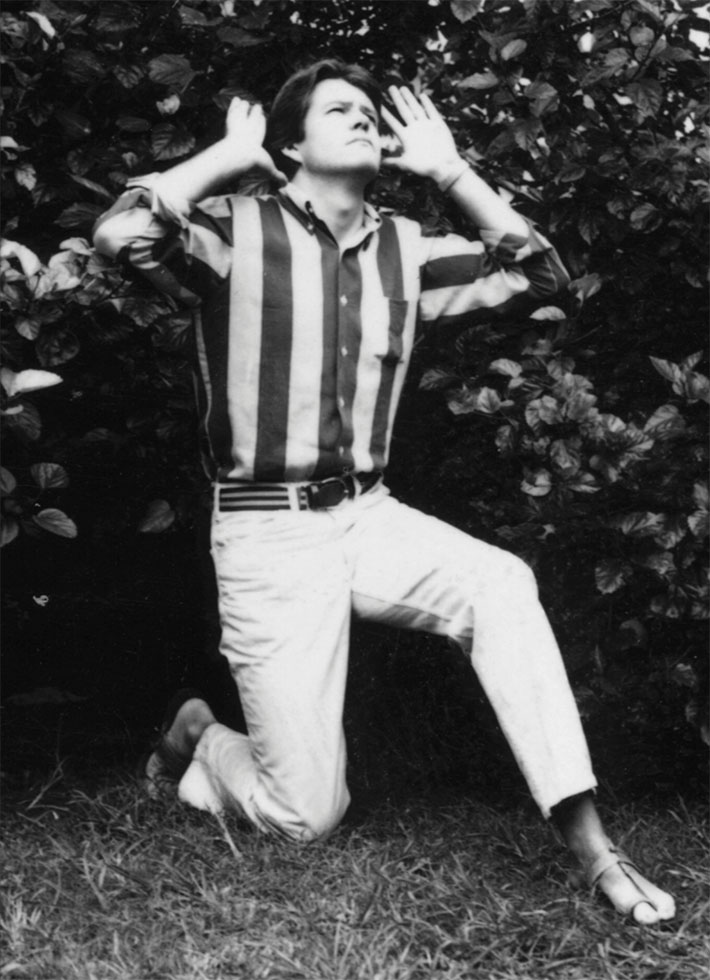

Music of the Spheres 1971

Performance as an act of audience

Black and white photograph 111.6 x 76.2 cm

Private collection

It was Pythogoras, who came up with the idea known as the music of the spheres: it had to do with musical sounds made by the heavenly spheres as they turned. He thought this was because the distance between heavenly bodies matched the length of strings that sound the different musical notes.

Johannes Kepler, thinking Pythogoras might be on to something, had a different take on it: he wanted to relate the speeds of the planets, to musical intervals and finding this not to be true, he stumbled onto the sublime instead.

Silent Manifesto 1971

Black and white photograph 111.6 x 76.2 cm

Private collection

A gesture from the conceptual zone: two speakers are directed at the street; a microphone is connected to an amplifier set at full volume. However, there is no sound. The microphone, bound in layers of cloth, has rendered the speakers mute.

The gesture, conceivably, has two explanations: an acknowledgement of John Cage’s famous lecture on “Nothing” – the opening line of which is “I’ve got nothing to say and I’m saying it” or, alternatively, it suggests that in cultural circles there is a sense that the manifesto’s history of defiance has played out and that henceforth the avant garde’s fate is cultural assimilation.

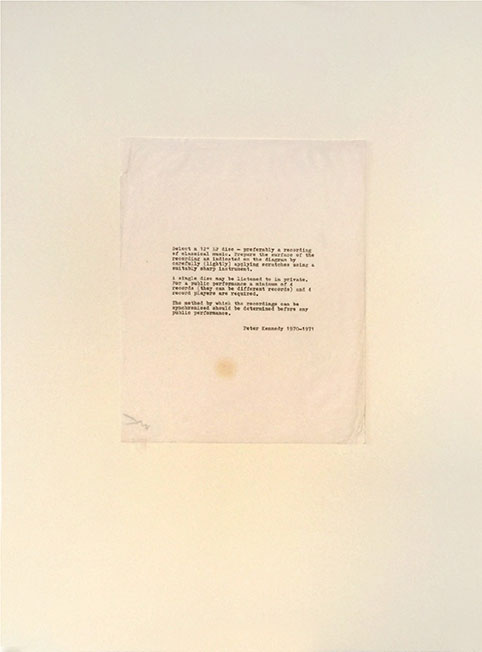

Prepared Record 1970 - 71

Quarto sheet, diagrammatic drawing on tracing paper, record

sleeve template with incisions.

Private collection

(The incisions reproduce the diagram and through them scratches are made to the record. The configuration allows for one or several scratch sounds to be heard with each revolution while at other points there are scratch-free interludes where the music is heard without interruption).

Quarto sheet instructions read as follows:

Select a 12” LP disc – preferably a recording of classical music. Prepare the surface of the recording as indicated on the diagram by carefully (lightly) applying scratches using a suitably sharp instrument.

A single disc may be listened to in private. For a public performance a minimum of 4 records (they can be different records) and 4 record players are required.

The method by which the recordings can be synchronised should be determined before any public performance.

Peter Kennedy, 1970-71